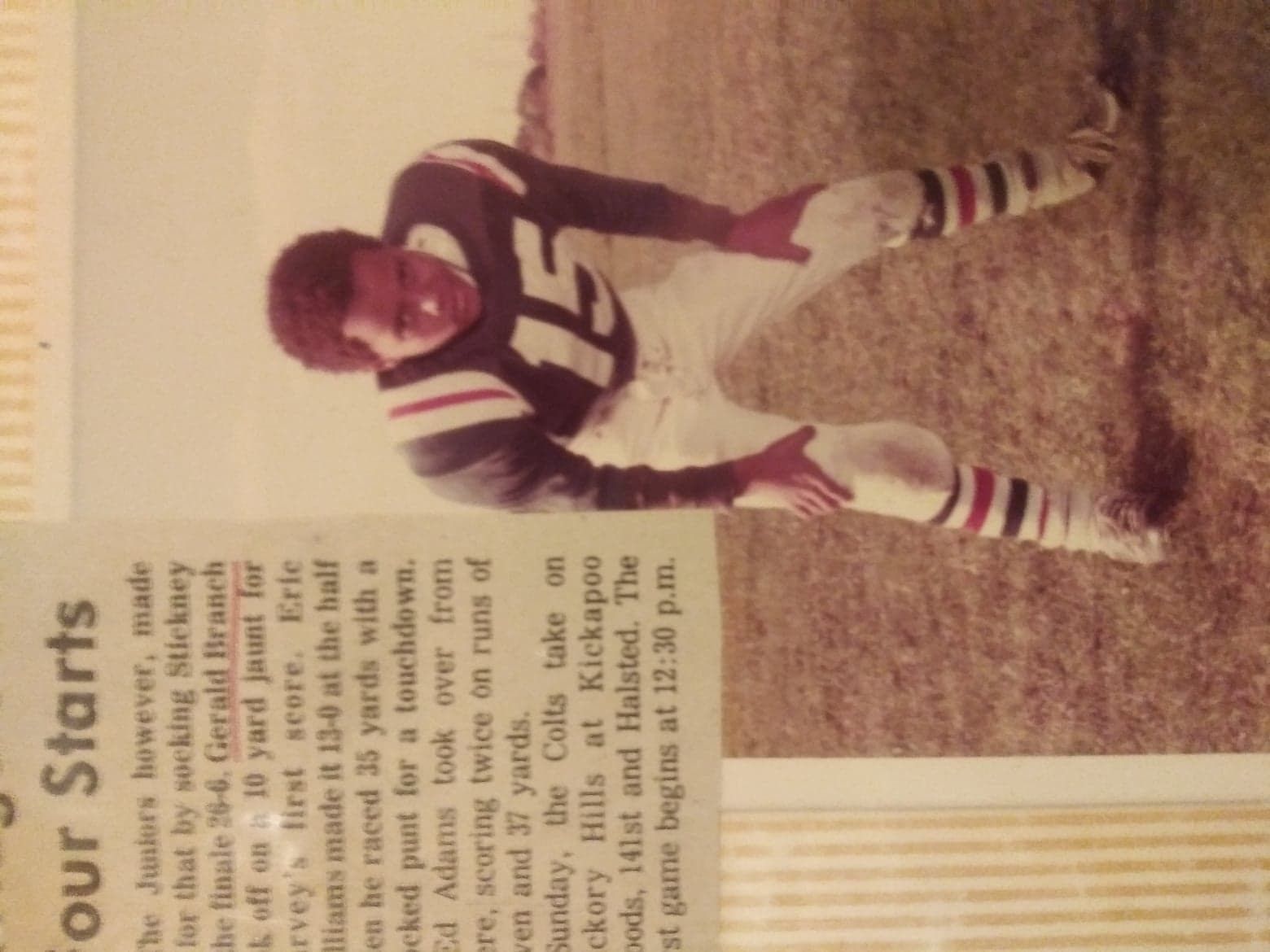

Framed

A visual narrative on Criminal Justice Activist, Gerald Branch-Bey.

This is his story.

This visual narrative shares the journey of Gerald Branch-Bey, a man who spent three decades incarcerated for a crime he maintains he did not commit. Through photos, documents, and key moments, the timeline traces Gerald’s life before, during, and after prison — revealing not only the challenges he faced but also the hope that carried him through.

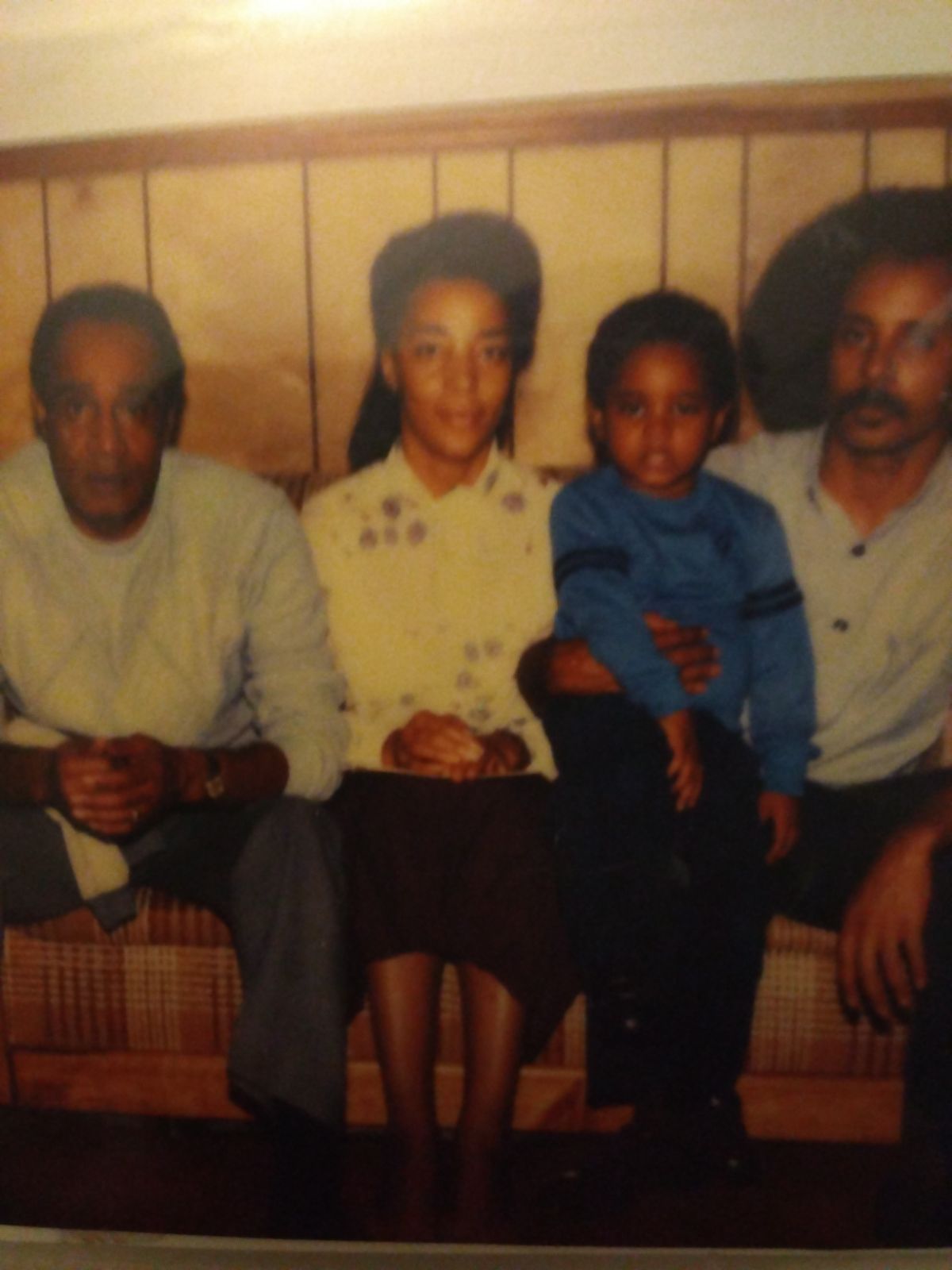

My family moved to Harvey, Illinois

As a young child, I lived in a neighborhood of

Chicago called Englewood with my father, my mother, and younger brother.

Where we lived back then, there was a lot of violence. I was around seven when my father decided he'd had enough. He packed us up and moved us to the suburbs for a safer life. We ended up in a place called Harvey on the Southside of Chicago. What we didn't know at the time, is that move would shape everything that came after.

“An idle mind is the devil’s workshop.”

.png)

Expelled from high school

But the move didn't keep me out of trouble. As a teenager, I gravitated toward the street life—the flashy cars, diamond rings, fur coats, and the respect that came from having all of that. Every now and then, I would come across people in town who would flaunt their luxury items. I saw people in town living that way, and I wanted it too.

It started with petty theft, but it didn’t stop there. By junior year, I was expelled for fighting and robbing a student.

After getting kicked out of high school everything started falling apart like a domino effect. Outside of school, I didn't have much place else to turn to. My grandma used to say, “An idle mind is the devil’s workshop,” I didn’t really get it then, but looking back, she was right.

I wasn't really doing anything with my time. and thoughts like "go rob somebody" or "steal this car" started creeping in. Getting kicked out of school put me on a path where crime seemed like the only way forward. Part of me thought, "Hey, this can be a career!" And so I treated it like it was.

My first time getting in trouble with the law

I was 14 years old when I got arrested for the first time. I was caught in a stolen car with that some friends of mine had taken. When I got out of jail the next day, all of my friends treated me like a king. Among them going to jail wasn't shameful; it was a sign that you were tough. People thought you were a real gangster. I remember them embracing me, buying me drinks, and giving me money. It was like a celebration,

My dad would always say to me, "Never get a criminal record, if you do, you are marked for life." But once I got arrested for the first time, that didn't mean anything to me. I was cool, I had respect, I had friends who had my back. If anything, it gave me an identity. However, looking back, he was right. That first arrest put a mark on me, one that would shape the rest of my life.

As I got older, it was always about finding ways to make a quick buck. But everything came crashing down when the police showed up at my parents' house in January of 1979.

My friend and I had been stealing what we called hot items—TVs, radios, jewelry; really anything valuable we could get our hands on. I would stash those items at my parents' house until we got a sale.

Eventually, my friend ended up getting caught. One day he shows up at my home handcuffed, with two officers asking for stolen items.

My father was home at the time. He didn't yell, didn’t cuss me out—he just looked at me. That silence weighed on me. I knew I’d brought shame into our house. It wasn’t just about me anymore—I’d dragged my family into my mess.

That night, I left. But when I tried to come back home, the doors were locked. It was freezing outside, and I had nowhere to go. That’s when it hit me — I’d pushed my parents too far. They weren’t letting me back in.

A couple of days later, my dad found me walking the streets, cold and tired. He pulled up, rolled down the window, and told me to get in the car. He drove me straight to the army recruitment center. He told me flat out, “You’re not coming back to the house. You’re going to sign up for the army or keep walking these streets.” That was the moment it hit me—I couldn’t keep living like this. Something had to change.

.png)

I joined the Army Reserve. The Army Reserve lets you serve close to home and continue to pursue goals such as education or a career. My MO was transportation, so I was driving the rigs, jeeps, and occasionally chauffeur colonels around.

Around the same time, I began a vocational program in auto-mechanics at Prairie State College. The program was a part of the CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) initiative where you get paid to learn a trade. These gigs added some structure to my life, but my mindset hadn't fully changed yet yet. I wasn’t there dreaming of becoming a mechanic — I was there for the money. I was still thinking like a hustler, still thinking like a criminal. I was getting older though, and I came to terms with the fact that I had to change my ways eventually.

According to court testimony, a Black man entered a sandwich shop in Midlothian, Illinois that morning. Court records indicate that this man entered the store, displayed a handgun, and demanded cash. After receiving the money in the cash drawer, he forced the cashier into a back room and shot her in the head. The victim survived.

Midlothian P.D. contacted neighboring police departments to look for possible suspects. They circulated the composite drawing to local law enforcement, hoping to find a photograph that matched.

The Markham Police Department responded, saying they had a mug shot of a potential suspect that resembled the drawing. Officers from Midlothian P.D. went to Markham P.D. to retrieve the photo. When they arrived, Markham P.D. handed them a photograph and told them it was of me. Midlothian P.D. then wrote my name on that photo so it could later be included in a photo array for the victim to identify the assailant.

It wasn’t until much later, when I and my public defender were sifting through a box of case files, that the truth came to light: the photo they had labeled as me wasn’t me at all.

The photo went into the lineup with my name written on the back. At the time, it seemed straightforward — the authorities, the victim, and everyone involved believed it was a photo of me. They asked the victim to look at the six photos to determine whether she could identify her assailant.

The victim was shown photographs of six different suspects, then positively identified the man depicted in Photo #5 as the person who robbed and shot her.

Based on this identification, Midlothian P.D. went before a Judge and procured a warrant for my arrest, based primarily on the fact that the Markham P.D. told Midlothian P.D. that Photo #5 was a photo of me.

%20(2).png)

I remember sitting in the passenger seat with my brother as he was driving when we saw several police vehicles behind us. I told him to pull over so they could pass. But when we stopped, the officers got out with their guns drawn.

They informed me I was being charged with armed robbery and attempted murder. I was in utter disbelief. But I made it my goal to obey their orders as multiple guns were pointed at me, and I could not afford to make any sudden movements out of the risk doing so could pose to my life. Police took me to the Markham Court Building for questioning.

I decided to cooperate, hoping to be released quickly. As the police interrogated me, their questions became increasingly specific. They asked me stuff like,

Are you certain?

Why aren't you certain?

Why don't you have proof?

They questioned me on my whereabouts on a random day over a month and a half ago. And I just couldn’t remember exactly where I had been. I realized the questions were leading. So I decided to invoke my 5th Amendment right and remain silent.

The Lineup

The police asked me if I wanted to join a corporeal lineup in which the victim would be asked to identify the perpetrator from a group of several people. I chose to participate to prove my innocence.

Following the lineup, I was escorted to a holding cell by a Cook County Sheriff who was in the mirrored room during the victim's identification. Before he put me in the cell he removed the hand-cuffs from my wrists. While doing so, he told me, "Don't tell anyone I told you this, but the victim did not identify you." He advised me to keep this information to myself.

At the time, I thought participating lineup would clear things up. Now, I wish I had never agreed to it — it’s a decision I regret to this day.

Several hours later, the Midlothian police officers came into the holding cell and told me that the victim identified me as her assailant, and that I was going to prison. I remember them shouting, "You're guilty!" "The victim identified you!" "You're going to prison for the rest of your life!"

They transported me to Midlothian police station. In the holding area, I came across another individual who was being held. He struck up a conversation with me to pass the time. I didn't know it at the time, but this inmate would play a major role in the case.

My attorney advised me to pursue a bench trial instead of a jury trial. The defense that my attorney presented at trial was an alibi defense strategy based on the testimony of my mother, placing me at home during the time of this offense. This is the only strategy my trial attorney presented. The prosecutor’s only witnesses were the victim and the jail-house informant. There was no evidence connecting me to the crime.

I was sentenced to 30 years in prison for armed robbery and attempted murder.

“Intelligence shall rule the world and ignorance shall bear its burden."

I appealed my case to get the ruling overturned, but the Appellate Court denied me. Then, I decided to take my case to the Illinois Supreme Court. They denied me as well.

At the same time, my parents were pursuing legal counsel to help me get out. They paid different attorneys over the years who said they would work on my case. My dad would pay anyone he could find. But the lack of knowledge on how to navigate and advocate for themselves as clients cost them a lot of time and money.

For a while, I had lost my focus. I had been to jail many times before, but the length of this sentence was something I could hardly fathom. I found myself going through the motions. Day-to-day life was very controlled.

One day, they were offering the GED test to prisoners. I remember hearing "Does anybody wanna take the GED test?" and I took it without studying. I passed it.

Passing that test made me feel good. It was an accomplishment. It made me want to aspire to do something better.

“That's where the sham came in at."

My family ran out of money to pay for attorney feeds. So I decided to file a case on my own. I filed a pro se petition for post-conviction relief. At the same time, I filed a subpoena duces tecum. I requested all of the documents from the police investigation. The Circuit Courts looked at my case and deemed that it had merit. They assigned me a lawyer free of charge; a public defender to help me on my case.

subpoena duces tecum

[sub·poe·na du·ces te·cum]

A Latin term meaning "appear and bring with you." is a court order that requires a person to produce documents, records, or other physical evidence for a trial or hearing.

I remember the first day I met my lawyer. She came in with a big ole box full of documents related to my case. She said, "That's yours." It felt so good to see that. That day, we spent hours going through the documents together.

In the stack was the photographic lineup from the investigation. As I flipped through it, I found a picture of a man I had never seen before — a photo labeled “#5” with my name written on the back. I froze. I showed it to my attorney and said, “This isn’t me.” She examined it closely, then looked up and said, “You’re right. That’s not you.”

I remember it like it was yesterday. I thought to myself, This is where the sham started. That's where everything went wrong.

That night, I brought the box of documents back to my cell and went through every page. I didn't sleep at all. For the first time in a long time, I felt hopeful for my future.

In addition to my petition for post conviction relief, I decided to file a Federal lawsuit. The lawsuit I filed was against the two officers who had arrested me based on the misidentification of Photo #5.

The officers filed a counterclaim to deny the allegations in my suit. However, when it was presented before the Judge, the Judge ruled in my favor, stating that I had a valid claim.

The attorneys representing the arresting officers proposed a settlement of $5,000 in order to resolve the case outside of court.

I rejected their offer. In my mind, settling felt like accepting defeat. This case was going to trial.

The same year, I began to focus on educating myself in law.

I started going to the law library and focusing on studying. I couldn't afford anymore attorneys so I felt like I had to educate myself on the law. I spent a lot of time trying to get intelligent so I could get out.

I had been taking advantage of the educational programs available to prisoners at the time. I received my Associate Arts Degree. I remember my parents came to the graduation ceremony. I saw them crying. It was another accomplishment that made me feel really good about myself. It made me think about what else I could achieve.

The officer who arrested me was subpoenaed to testify in court, marking the first time I saw him since the day of my arrest. It was also the first time I made a physical appearance in court since the trial resumed.

After everything was finished, the Judge asked, "Do the parties want to supplement any other evidence before I make my ruling?"

That gave me the idea to supplement my case with more information. My lawyer representing me at the time said we would like to add more evidence before a decision was made. As a result, the Judge did not make a decision at that time and my case continued.

My petition would lay dormant for three years.

While my case sat untouched, I used the time to strengthen it however I could. I spent hours in the law library, digging through books and case law, searching for anything that might give my claims more weight.

Part of my argument was that I was subject to ineffective assistance of council before I was convicted. My appellate attorney never visited me, never showed me the photographic lineup, and never gave me the chance to see the misidentified photo for myself. Because of that, I couldn’t challenge it or say, plainly, “That isn’t me."

Although the Court acknowledged that Photograph #5 wasn't me, they still refused to release me. On the basis that newly discovered evidence which discredits a witness is not grounds for a new trial.

res-judicata

[res ju·di·ca·ta]

A Latin term meaning "a matter judged". This doctrine prevents a party from re-litigating any claim or defense (or issue) already litigated.

I was disappointed, but I refused to lose hope. I appealed this case to the Appellate Court.

Offered $5,000 to settle out of court, I denied it because it would mean that I would be admitting guilt. I went to trial as a plaintiff but they still denied me.

It was ruled to be an error on the officer's part, because of that, the jury ruled in favor of the police.

It took two years for my appeal on the 1993 decision to be reviewed, and it was denied. After that rejection, I decided to take it to the Supreme Court.

Later that same year, the Supreme Court denied me as well. At that point, I had no more courts to go to. They call that an exhaustion of state remedies.

.png)